by Zad Datu

In the 40s, American psychologists, B.F. Skinner had his philosophy about human behaviour challenged – a philosophy insisting that all behaviours including that of humans are results of reinforcements. The white haired, round spectacled professor explains that people do not routinely travel to their local gambling club because they enjoy every moment of pulling down on jackpot sticks, but rather a result of the built in schedule of the reinforcement.

The foundations of his philosophy are his experiments on training animals, mainly pigeons, to perform certain behaviours such as pecking on a button or turning around. Each hungry pigeons are placed in a box attached to a feeding machine, dubbed the Skinner box, in which the pigeons would be rewarded with a piece of corn whenever they perform whatever behaviour Skinner wishes to programme into the birds.

Superstition is a uniquely human behaviour, so our behaviours can’t be the results of reinforcement after all – this was the statement that challenged Skinner’s philosophy.

Skinner responded by modifying the experiment so that rather than rewarding the birds upon a specific behaviours, the machine feeds them one piece of corn every fixed interval or randomly. Skinner observed that the pigeons developed repetitive behaviours. Some were jumping up and down, some bobbing their heads, some flapping their wings, and all other sorts of obnoxious behaviours. Skinner observed that whatever movements the pigeons happen to be carrying out when the first corn piece popped out, the pigeons would repeat them hoping to be rewarded again, which coincidently out pops another piece.

That bird brains of theirs fooled themselves into thinking that it is these movements which triggers the reward, repeating them as the machine continues to release more food. This, Skinner concluded, demonstrates superstitious behaviours in animals.

So here’s the thing: superstition isn’t a uniquely human occurrence. Superstition also exists within animals. Animals and humans have to be natural in detecting patterns– to detect the patterns of their potential prey, the pattern in the climate which promotes rich vegetation, or the patterns of predators to keep out of harm’s way – to make predictions for their very survival. Combine this necessity with a complex brain, they beauty and brilliance of mathematics emerges, as counting and measuring is needed for more accurate predictions. But if this brilliant combination is accompanied by horrible reasoning, out emerges a side-effect, best exemplified with people who self-convincingly conclude that the faces they make out from still photos of smokes, and spoken words out of static noise from sound recordings of empty quiet rooms are signs of spirits. Pigeons and humans alike, when one seem to detect patterns which aren’t really there, yet remain convinced, this is superstition.

|

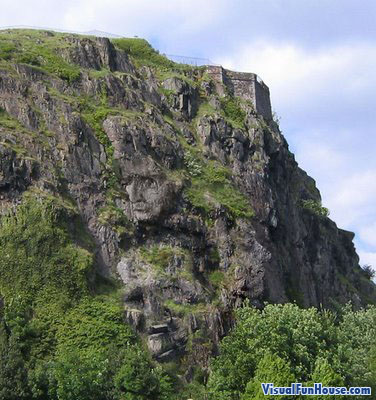

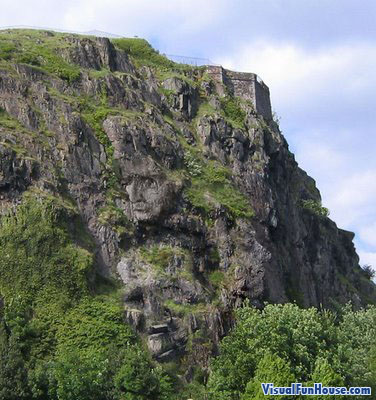

| Natural rock formation which seems to conjure up images due to our innate pattern detecting brain. |

Athletes and club supporters are easy example of this bird-brain behaviour. “The last two times I wore this underwear during a match, I performed really well, and I won. I’m going to wear it again for my next match to increase my chances,” some athletes may have in their mind. “I was holding my pee when my team was doing really well. But then when I decided to visit the loo to let it out and came back, they started performing really badly. Next time I will never go to the loo during a match,” some club supporters would say.

Then there is the folk beliefs type of superstition. It is a product of our ancestral elders storifying false consequences of undesired customary bad habits to the young ones, preventing them from developing.

“Do not harm animals, or your child will be born crippled.”

“Do not shake your legs when you are sitting down, or you will always be in debt.”

“Do not sit on the porch and stare outside,” a mother would advice her daughter, and if the daughter questions why, “You will get married at a late age,” would be the given reason.

“Do not sing in the kitchen,” a mother would advice her daughter. “Why?” the daughter asks, and the mother would answer “Or you will marry an old man.”

“Do not cut your nails at night,” a mother would advice her child. “Why?” the child asks. “You ask too many questions!” the mother snaps. Actually, there are quite a number of reasons for this. One of them is that it will shorten one’s life.

These are just some of the pantang larang, or prohibitions, that we have in Malay folk beliefs.

Pontianak, a Malay equivalent of a female banshee-like-vampire; toyol, a goblin-like-spirit invoked from a human foetus; orang minyak or “oil man”, an oily women-raping hominid capable of disappearing into thin air; mawas, the Johorean (Malaysia) equivalent of Bigfoot; and orang pendek or “short man”, an Sumatran (Indonesia) miniature Bigfoot are Malay cultural examples of another category of superstition – folklore, be it just a creature, or creatures with a well developed tale behind its origins.

The existence of an upright-walking, furry, 10 feet tall ape and gigantic flying birds of prey sounds very plausible since they do not contradict with biological knowledge and that there already are similar known existing creatures. In fact, there was an ape species called Gigantopithecus which lived in Asia about 1 million years ago measuring up to 10 feet tall and 540 kg – closely resembling the North American Bigfoot or Sasquatch and its other varieties (including Himalayan Yeti, Australian Yowie, Brazilian Mapinquary, South American Maricoxi, Chinese Yeren, Caucasus Mountain’s Almas, Kenyan Chimiset, Siberian Chuchunaa, Japanese Higabon and Vietnamese Nguoi Rung), and a Family of birds-of-prey called Teratorns which lived in North and South America roughly throughout 20 to 2 million years ago with wingspans measuring up to 12 feet and weighing 15 kg – closely resembling the Native American’s mythical creature, Thunderbird. As of the Scottish Loch Ness Monster, they perfectly resemble the Pleisiosaurs – again, plausible. One version of the Chupacraba is simply a hairless goat-blood-sucking dog-like animal – very plausible indeed.

So, unlike the physically and biologically implausible existence of garlic-allergic sunlight-allergic cross-shaped-allergic non-shadow-casting non-reflection-casting bat-morphing human-blood-sucking murderous caped crusaders, or green-coated cocked-hat-wearing wish-granting elderly bearded Irish dwarves with pots of gold hidden at ends of rainbows, “Bigfoot, Thunderbirds and Loch Ness monster, aren’t superstitions after all” you may ask. Wrong! Not only did their mythical existences develop long before the discovery and long after the extinction of their prehistoric counterpart, but more importantly, unlike ghost and daemons of the Middle Ages, modern day Bigfoot, Thunderbirds and Loch Ness monsters have not been discovered, studied upon, well documented, peer reviewed, published, and presented with specimen as evidence and listed in a biological taxonomy of life. The seemingly implausible mysterious life forms capable of crawling its way into people, possessing them, distorting their physical appearances, perceptions, behaviours and well being, and are always around us yet invisible to the naked eye, capable of moving through walls were scientifically uncovered to be smaller than the size of a pin head which we now call microorganisms or germs. “To be possessed by daemons” in the medieval times now translates to “to be infected by germs”, or simply “to fall sick”. Psychiatric illnesses, the bizarre alien hand syndrome and sleep paralysis, on the other hand, are reminiscence of the more extreme cases of daemonic possessions.

Sleep paralysis is a rather particularly interesting one. It is where the natural paralysing mechanism that takes place during sleep, necessary to prevent us from physically acting out our dreams, continues to function upon waking up or starts functioning upon falling asleep, resulting in losing total physical control including speech while our mind remains awake and aware. If that doesn’t terrify you, then hallucinations of two shadowy hominid figures pressing down onto your chest just after a few seconds of tremor accompanying the paralysis surely would. At least, that’s what I experienced before breaking free. Most do not break free and fall back asleep to later wake up being certain it was all real, traumatised by the mysterious murderous attack. This is where folklores of daemons sitting or pressing on a sleeper’s chest such as the Scandinavian mare dating back to the Norsemen Middle Ages are bred into cultures. Cultures around the world put the blame of these eerie experiences onto their own invented daemons – the English and Anglo North American Old Hag, the Chinese guǐ yā shēn, Japanese kanashibari, Korean gawi nulim, Mongol khar darakh, Vietnamese ma đè, Tamil Amuku Be, Turkish karabasan, Icelander lidércnyomás, New Guinean Suk Ninmyo, Nepalese Khyaak, Ethiopian dudak, Zimbabwean Madzikirira, Swahilian jinamizi, Persians bakhtak, Greek Mora, Vrachnas or Varypnas, and majority of Muslims including here in Malaysia blames the Shiatan and evil Jinns. The most modern folklore, yet science fiction, manifested from sleep paralysis, primarily in the US, puts the blame on a human-skeleton-resembling extraterrestrials – the folklore of alien abduction.

Aside from that, the sightings of Bigfoot, Thunderbirds, Loch Ness monsters and Chupacrabas, or any other creatures for that matter, are separate matters from the plausibility of their existence. The sightings are separate superstitions on their own, not any less superstitious then the sighting of Einstein and Beethoven having a delightful conversation at a coffee shop in this current day, taking note that Einstein and Beethoven were real existing people.

The next topic in question is whether it is closed-minded to dismiss

superstitious claims or is it simply gullible to accept them. This, I leave it for the next

article on superstition to tackle.

Succeeding linked article:

What Lay People Should Know about Superstition – Open Minded or Gullible? (argumentative)